You are here

Well-Hidden Perk Adds Up To Big Money for Executives

Deferred-Compensation Plans Give Tax Benefits, But Are Poorly Disclosed and Add to Liability

This article is part of a package of Wall Street Journal stories on the early-2000s corporate scandals that won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting; that package can be found here: http://www.pulitzer.org/works/2003-Explanatory-Reporting. It also is part of a series of stories that won the 2003 George Polk Award for Financial Reporting; a list of those articles is available at http://web.archive.org/web/20070806115216/http://www.brooklyn.liu.edu/po....

Last year, John R. Stafford, chairman of pharmaceutical giant Wyeth, earned $1.8 million in salary. He also was awarded a $1.97 million bonus, restricted stock valued at $724,283 and 630,000 stock options.

That much shareholders can learn from glancing at the company's proxy.

But buried in footnotes are clues that Mr. Stafford, 64 years old, is entitled to another pot of money worth millions of dollars. He participates in a retirement program that allows executives to set aside, pretax, as much as 100% of their cash compensation. Wyeth guarantees them a 10% return on their deferred pay.

How valuable is that?

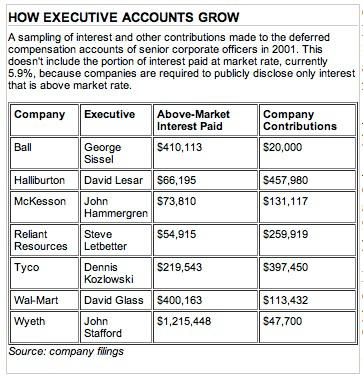

Last year Wyeth paid Mr. Stafford $3.8 million in interest on a deferred-compensation account valued at $37.75 million, according to calculations based on information in the company's public filings. On top of that Wyeth gave him an additional $47,700 in matching contributions.

Super-sized salaries, sweetheart loans and generous stock options have come under fire as corruption scandals have prompted heavy scrutiny of executive compensation. But lurking behind those benefits is another goody swelling the pay packages of top executives. With hefty infusions of cash from their employers, senior officials at many large companies are accumulating big sums in their deferred-compensation accounts. It adds up to a massive, ever-ballooning and in most cases unknowable corporate liability.

All this means that the lawmakers and corporate compensation watchdogs who have railed against what they consider to be bloated executive pay in recent months have largely overlooked one of the biggest sources of executive compensation, worth a total of tens of millions of dollars to top officers.

"It's the untold story of executive compensation," says Judith Fischer, managing director at Executive Compensation Advisory Services, an Alexandria, Va., consulting firm. "You can't see how big it is, you can't see how it's growing. You can't see what the total value to the executive is."

On the surface, it looks pretty routine. The deferred-compensation programs appear to be nothing more than savings plans that let executives reap the tax advantages of deferring some of their pretax pay.

There is, however, a crucial twist or two that makes these plans especially rich. Employees typically are allowed to put no more than 10% of their pretax pay into 401(k) retirement plans. But top executives enrolled in these souped-up plans usually can sock away all of their salary and bonuses.

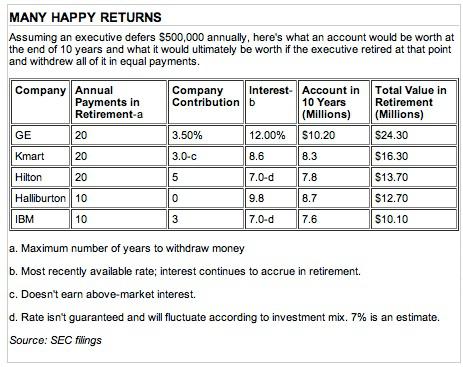

Then the company makes a contribution, sometimes a percentage of what the executive kicks in, and frequently guarantees a rate of return that continues to be paid even after the executive retires. Those rates vary company to company, but they are often higher than what investors make in the stock market even in good economic times. So while many employees recently have seen the value of their retirement accounts wither, executives who have put off taking big chunks of income are sitting pretty.

Among the companies with generous plans are Xerox Corp., Walgreen Co., Lucent Technologies Inc., AT&T Corp. and Diebold Inc., all of which guarantee senior executives above-market annual returns, currently defined by the Securities and Exchange Commission as interest of more than 5.89% a year.

For the most part, public filings only hint at a company's total price tag for deferred compensation, and the tidbits are buried in footnotes and oblique language. Companies are required to disclose only a piece of what they promise executives -- but not their total annual contributions or even how many employees participate in the plan. Just to estimate how much an executive is getting often requires access to a company's filings going back years. Publications distributed by at least two federal agencies also are necessary to fit together the puzzle pieces. It's beyond the experience, and certainly the patience, of most shareholders.

Fuzzy disclosure by U.S. companies is entirely legal. Still, incomplete information can stymie the efforts of shareholders, regulators or anyone else trying to calculate an executive's full compensation. It also can keep them from being able to understand deferred compensation's impact on a company's bottom line. An examination of hundreds of public filings by The Wall Street Journal found that vague disclosure of deferred-compensation plans is pervasive.

'Exponential Growth'

Deferred-pay programs, often called top-hat plans, have been around for decades. A big push to beef them up came in 1994, when Congress enacted a law intended to rein in the cost to taxpayers of runaway executive pay. The law barred companies from taking a tax deduction on compensation in excess of $1 million a year for any currently employed individual. So companies encouraged executives to postpone taking the amount of their pay in excess of $1 million until after they left the company or retired.

Company contributions into individual top-hat accounts are usually many times larger than what they put into regular 401(k) retirement plans of rank-and-file employees.Electronic Data Systems Corp., for instance, made a $355,078 contribution into the deferred-compensation account of Chief Executive Richard H. Brown in 2001, according to the company's proxy. Mr. Brown deferred $300,000 of his $1.5 million salary and $1.2 million of his $7 million bonus.

Ralph Larsen, former chief executive of Johnson & Johnson, from 1999 to 2001 received $5.2 million in company contributions to his deferred-compensation account, on top of $8.9 million in salary and bonus, according to the company's latest proxy. Mr. Larsen's account would have an estimated value of $33.3 million when he retires, the proxy notes. Both companies declined to discuss their deferred-compensation plans.

For shareholders, understanding contributions can be confusing because companies use so many methods of calculating them, and then disclose little about their methodology. At some companies, contributions are awarded at the discretion of the board. Other companies have formulas for determining contributions. When Sears, Roebuck & Co. executives postpone taking bonuses and long-term incentive pay, they get a contribution equal to 20% of the amount deferred. If Boise Cascade Corp. executives agree to put their deferred pay into company stock, they get a 25% matching contribution. Both companies say the contributions help retain executives.

Companies also increasingly are offering executives guaranteed rates of return. The approximately 200 executives in Boise Cascade's plan receive interest payments equal to 130% of Moody's average corporate yield, that comes to about 8.9% today. Harrah's Entertainment Inc.'s plan has provided 12% to 13% returns in recent years. Halliburton Co. paid an average of 9.8% on deferrals last year. AT&T pays a minimum rate of 2% above the yield on a 10-year Treasury note, or about 7% last year.

AT&T provides above-market returns in order "to be competitive with other major corporations and their compensation policies," according to a spokesman.

Another beneficiary of above-market interest is Richard J. Meelia, chief executive of Tyco International Ltd.'s health-care unit. He was paid $624,519 in salary last year, a $7.6 million bonus and deferred $6 million of his compensation, according to the company's proxy statement. The company says executive accounts recently received interest of about 9.1% a year. At that rate Mr. Meelia, 53, can expect to accumulate more than $8 million in interest over the next 10 years, even if he defers no more of his income.

In another flourish recently added to some plans, companies permit executives to defer gains from exercising stock options, swelling the size of the accounts. At Sears, which started doing so in 1999, the gains earn returns based on the performance of Sears stock. The treatment of stock-option gains varies at other companies. Some make matching contributions or grant above-market interest on deferred stock-option gains.

"The exponential growth in compensation being deferred is being jacked up by the ability to defer gains on stock options," says Ms. Fischer, the compensation consultant.

Tiers of Retirement Plans

Many companies have more than one kind of top-hat plan. Less elite varieties, often known as "mirror" or "make up" plans, simply are meant to supplement 401(k) plans, which allow workers to defer some salary and receive company contributions.

Tax laws limit the amount of money employees can annually contribute to 401(k) retirement plans. The idea was to prevent retirement programs from favoring highly paid employees. Companies use the make-up plans to sidestep that rule, by allowing executives to set aside additional money.

Kmart Corp., for example, lets most of its highly paid employees put up to 10% of their pay into 401(k) plans. But a Kmart executive earning $200,000 can't put 10% of his pay into his 401(k) because the law limits the amount an individual can contribute to $11,000, if the employee is under 50, or $12,000, if he or she is 50 or older. The executive, however, can make additional payments into a deferred-compensation plan to bring him up to the full $20,000, or 10%, of his pay.

Meanwhile, the highest-paid executives at Kmart can defer 100% of their salaries, as well as stock, restricted stock and stock-option gains. These executives are entitled to a company match of up to 3% of their salary, plus discretionary awards by the board's compensation committee "for any reason whatsoever," according to the plan, which is attached to the back of the company's annual financial report filed with the SEC in 1999. They can earn a rate of five percentage points above 10-year Treasury notes, or currently about 8.6%.

Company filings show that in 2000 Kmart credited Floyd Hall, its 64-year-old former chief, with $207,763 in interest on his deferred compensation, plus $385,354 in company contributions to his retirement and deferral accounts. Mr. Hall said in an interview that from 1996 through 2000, he deferred a total of $4.47 million of his compensation and received a total of $1.09 million from Kmart in company contributions and interest. The pay he deferred was compensation that Kmart would otherwise not have been able to deduct from its taxes that year, Mr. Hall said.

Benefits for the Company

Deferred-compensation plans differ from 401(k) plans in another significant respect. An employee's 401(k) account is kept in his or her name and is segregated in a special account that the company can't dip into. Although participants in top-hat plans have accounts, they really are just bookkeeping devices, IOUs to the executives from their companies.

The plans are set up this way, because in order not to be taxed, the executive cannot actually have the money in his name. So even if the company tucks some of the money away in a trust, which some do in order to cover their liabilities, the money still is kept in the company's name.

Because they hold on to the money, companies sometimes argue that they benefit from top-hat plans. Kmart's arrangement, says Mr. Hall, was "very well thought through" because it allowed the company to use the money. The company "could have borrowed it cheaper," Mr. Hall acknowledges, but employers have to provide a "sweetener" to executives who otherwise could invest their money elsewhere and potentially get a higher return.

Wal-Mart Stores Inc. uses its deferred compensation "for capital expenditures, for growth and reinvesting in the business," says spokesman Jay Allen. Deferred-compensation programs, he adds, are a necessary recruiting tool. "We're the largest company in the world, and we need to attract and retain a senior management team that reflects that," he says.

A spokesman for Walgreen says its deferred-compensation plan, which grants above-market interest, "helps tie the individual to the company. It builds loyalty to the company." In fact, some companies allow executives to keep interest payments or matching contributions only if they stay put for typically three to five years.

Top-hat plans amount to a huge and ever-growing liability that is rarely well disclosed to shareholders. But some companies dismiss the importance of their deferred-compensation liability by pointing to assets they have set aside to offset the obligation, often in a trust. Tyco, for one, notes that it has set aside assets in a trust to cover its deferred-compensation program liabilities of $175 million. "The fair value of these assets exceeds the plan's liabilities," says Tyco spokesman Gary Holmes.

But even when companies set aside money to pay their deferred-compensation costs -- and they are not required to do so -- they usually are not obligated to use it for that purpose. Also, they may not have set aside enough to account for the cost of company contributions and compounded annual interest over the course of many years, says an SEC official who declined to be named. "It isn't a neutral on the balance sheet," he says. "It's a tremendously large obligation."

Getting Out the Magnifying Glass

Back in 1992, the SEC beefed up disclosure rules for executive pay and perks, and companies began disclosing the annual cost of plane rides, financial planning and moving costs -- entitlements worth tens of thousands of dollars for some executives.

Deferred compensation, which can be worth millions a year to executives, was dealt with only in passing by the new rules. Companies are required to report only guaranteed above-market interest paid annually into the accounts of the five highest-paid executives. They are not required to disclose interest paid below that rate or any gains pegged to stock funds, hedge funds or other investments with fluctuating returns. Such investments, of course, may have lost money recently.

And although companies are required by the SEC to disclose agreements with senior management, which includes deferred-compensation plans, some don't. Tyco, for example, hasn't filed its deferral plan. Mr. Holmes, the company's spokesman, says the company's new management is reviewing its disclosure practices.

David D. Glass, the chairman of the executive committee of Wal-Mart's board, earned $400,163 in above-market interest on his deferral account last fiscal year, according to the company's proxy. The company did not have to disclose the additional interest that was paid at market rates. Mr. Glass also received a company contribution of $113,432.

For shareholders, this all means that deciphering deferred-compensation programs, and calculating who is getting how much, can border on the impossible.

To figure out how much GE paid into retired Chief Executive John F. Welch Jr.'s deferred compensation plan in 2001, for example, it helps to have handy the company's proxy, attachment 10(x) to its annual financial report, the IRS's Revenue Ruling 2001-58, a copy of SEC Regulation S-K, Item 402(b)(2)(iii)(C) and, of course, a calculator.

Mr. Welch, 66, who retired in September 2001, earned $3.4 million in salary and $12.7 million in bonus that year. GE's proxy filing doesn't say how much of his compensation he deferred. It does, however, note that the company paid him $1.25 million in above-market interest. In the attachment to its annual financial report, GE notes that it paid top executives 12% interest on their 2001 deferred salary. Using those figures, plus the market interest rate for December 2001 of 6.08% -- Regulation S-K defines market-rate interest as up to 120% of the rate published monthly in the IRS publication -- investors could calculate that Mr. Welch received another $1.3 million in market-rate interest. The proxy also states that GE made a $340,375 contribution to Mr. Welch's retirement and deferred compensation plans, although it doesn't fully explain how the company arrived at that figure. It all adds up to an additional $2.87 million, or 17.8%, of Mr. Welch's 2001 cash compensation. And that's an estimate.

GE declined to comment on Mr. Welch's deferred compensation.

Divining the total price tag for a company's deferred-compensation plan can be equally frustrating. Companies are not required to disclose it and so investors cannot see how the cost is growing. Often companies lump it into more general liability categories on their balance sheets. Verizon Communications Inc. includes it in the figure for the cost of pensions for rank-and-file employees. GE includes it in the "other liabilities" line.

David Frail, a GE spokesman, says the company's liability for its deferred-compensation plans is $2.4 billion. He says that the company does not disclose the number in its public filings because the amount is not significant. "Frankly, it's relatively small for a company with half a trillion dollars in assets," he said in an e-mail.

Sometimes, even companies have trouble figuring out their own tabs for deferred compensation. Halliburton spokeswoman Wendy Hall said in an e-mail that the "total liability" for the Halliburton Elective Deferral Plan was $53.4 million as of the end of June 2002. But that figure doesn't tell the whole story because it does not take into account future interest costs to the company. What's more, Halliburton has other deferred-compensation plans, including some inherited through mergers, Ms. Hall subsequently said. She added that the total liability for the company's entire deferred-compensation program is "not publicly disclosed information."

Special Privileges

For most executives, the one potential drawback to socking away large sums in top-hat plans is that if a company becomes insolvent, they may have to get in line with other creditors. But executives have some protection against this problem because they have fairly easy access to their money.

Tax law dictates that employees must pay a 10% penalty if they make early withdrawals from their 401(k) plans. But when it comes to deferred compensation, the IRS only says that executives must have "substantial limitations or restrictions" on their ability to get the cash.

As a result, companies are free to determine the penalties for early withdrawal themselves. Many companies do impose penalties, also known as haircuts, of 10% or in the case of Verizon and some other companies 6%. But some companies impose no penalties, so long as, when making the deferral, the executive notifies the company when he or she will take out the money. Both Kmart and Merrill Lynch & Co. allow executives to defer compensation for as little as one year, according to their plans.

Some companies also design their plans so that if there is a change in corporate control or the company hits the skids financially, they will either pay out the money to executives or guarantee it, except in the case of a bankruptcy. Under the terms of Halliburton's deferred-compensation plan, for example, the company is required to automatically turn over account balances to executives within 45 days if the company's credit-rating were to fall below investment grade.

Enron Corp. had about 285 executives enrolled in its deferred-compensation program and had accumulated roughly $220 million in related liabilities by the time it filed for bankruptcy-court protection last Dec. 2. One of Enron's plans guaranteed executives a minimum 12% return on deferrals.

The company allowed executives to take money out of their deferral accounts by paying a 10% penalty on the money withdrawn. In the year before the bankruptcy filing, about 140 executives with the title of managing director or above deferred nearly $28 million of their pay. About three dozen of those executives withdrew a combined $32 million from their accounts in the same period, bankruptcy-court documents show.

Among the executives who withdrew funds was Mark Frevert, former chairman and chief executive of Enron Wholesale Services. During the 12 months before Enron filed for bankruptcy, Mr. Frevert deferred $3.4 million of his pay, but he withdrew $6.4 million from the account he had accumulated over time.

Mr. Frevert's attorney, J.C. Nickens, confirms the withdrawals but adds that his client "ended up losing a lot. He put ... a lot of money into that particular vehicle because it was advantageous, obviously, and because he believed in the company."